The Burning of Knockcroghery, June 20th 1921

The early hours of Tuesday 21 June 1921 were clear in the skies over County Roscommon, save for a few light clouds drifting westwards from Lough Ree that perhaps heralded the coming Summer Solstice. At one o’clock in the morning, most people in Knockcroghery were fast asleep. But within half an hour, every man, woman and child in the village was to awaken into a horrific nightmare.[i]

Those living at the south of the village were the first to hear the four lorries roaring up the main road. There were at least four Black and Tan soldiers in each lorry and they had almost certainly driven direct from the military barracks in Athlone.

The lorries screeched to a halt beside St. Patrick’s Church and the Tans jumped out. Dressed in civilian clothing, they were also drunk and armed. The soldiers fixed masks to their faces and prepared to unleash utter hell on the village.

They began firing their guns into the sky as the first petrol bomb was hurled onto a thatched cottage.

There were fifteen houses along the main street of Knockcroghery on the eve of the burning, most of them single-storey thatched cottages. By the morning, all bar four had been reduced to ash.

Few villagers can have known why the soldiers were in Knockcroghery that night, although perhaps word had already spread about the assassination of Brigadier General T.S. Lambert earlier that evening.

Lambert, a decorated veteran of the Western Front, had been in charge of the 13th Infantry Brigade at Athlone since December 1919. He was driving back to the barracks from a tennis tournament in Glasson when ambushed near Moydrum by a group of six armed men. His wife, who was driving the car, tried to outrun the men and a gun opened fire. General Lambert was shot in the neck and died 90 minutes later at the Military Hospital in Athlone. Another passenger, Mrs. Challoner was wounded in the face by pellets.[ii]

Those living at the south of the village were the first to hear the four lorries roaring up the main road. There were at least four Black and Tan soldiers in each lorry and they had almost certainly driven direct from the military barracks in Athlone.

The lorries screeched to a halt beside St. Patrick’s Church and the Tans jumped out. Dressed in civilian clothing, they were also drunk and armed. The soldiers fixed masks to their faces and prepared to unleash utter hell on the village.

They began firing their guns into the sky as the first petrol bomb was hurled onto a thatched cottage.

There were fifteen houses along the main street of Knockcroghery on the eve of the burning, most of them single-storey thatched cottages. By the morning, all bar four had been reduced to ash.

Few villagers can have known why the soldiers were in Knockcroghery that night, although perhaps word had already spread about the assassination of Brigadier General T.S. Lambert earlier that evening.

Lambert, a decorated veteran of the Western Front, had been in charge of the 13th Infantry Brigade at Athlone since December 1919. He was driving back to the barracks from a tennis tournament in Glasson when ambushed near Moydrum by a group of six armed men. His wife, who was driving the car, tried to outrun the men and a gun opened fire. General Lambert was shot in the neck and died 90 minutes later at the Military Hospital in Athlone. Another passenger, Mrs. Challoner was wounded in the face by pellets.[ii]

General Lambert was evidently a popular figure in the barracks and news of his death sparked an instant demand for reprisals from those under his command. His assassins were believed to have escaped in the direction of Lough Ree and to have vanished in boats. Misinformed British intelligence agents then delivered the catastrophic verdict that the killers hailed from Knockcroghery.

Four hours after the General’s death, the Tans began to burn the village. They gave the occupants no warning. The houses were simply set on fire and those inside had no option but to flee outside in their night clothes. With the enraged Tans loosing off constant fusillades with their revolvers and rifles, the majority ran through the fields at the back of the house and sought refuge on Hangman’s Hill, the ominously named stony ridge which protects the village from the easterly winds sweeping in from Lough Ree. [iia] Some managed to grab their bank books as they fled, but all their title deeds and personal belongings were engulfed in the flames.

The Rev. Bartholomew Kelly was wide awake when the Tans thundered through his front door and demanded he leave the building. At first he refused but when he saw the men sprinkling petrol over his furniture, he leapt through his bedroom window, dropped 12ft onto a shed, rolled to the ground and concealed himself until the mob had left. As it happened, the slate roof on the building saved his house from complete annihilation but his widely admired library was destroyed.

Four hours after the General’s death, the Tans began to burn the village. They gave the occupants no warning. The houses were simply set on fire and those inside had no option but to flee outside in their night clothes. With the enraged Tans loosing off constant fusillades with their revolvers and rifles, the majority ran through the fields at the back of the house and sought refuge on Hangman’s Hill, the ominously named stony ridge which protects the village from the easterly winds sweeping in from Lough Ree. [iia] Some managed to grab their bank books as they fled, but all their title deeds and personal belongings were engulfed in the flames.

The Rev. Bartholomew Kelly was wide awake when the Tans thundered through his front door and demanded he leave the building. At first he refused but when he saw the men sprinkling petrol over his furniture, he leapt through his bedroom window, dropped 12ft onto a shed, rolled to the ground and concealed himself until the mob had left. As it happened, the slate roof on the building saved his house from complete annihilation but his widely admired library was destroyed.

The Catholic clergyman then sought sanctuary in the Presbytery, where many of the town’s children and elderly were hiding. However, when an attempt was made to set the Presbytery alight, the occupants were directed to the Protestant Rectory.[iii] The Rev. Humphreys and his wife ushered in everyone they could find and began handing out their clothes to the terrified and half-naked villagers.

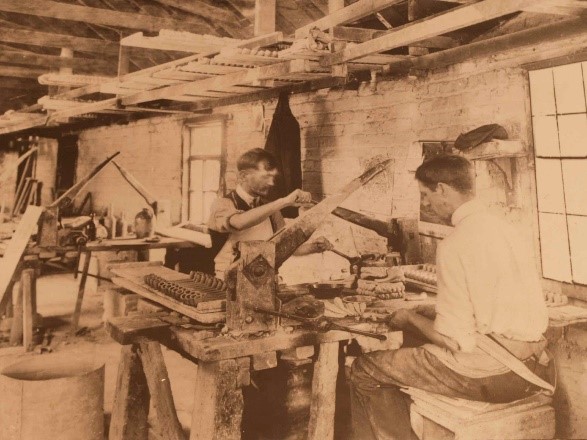

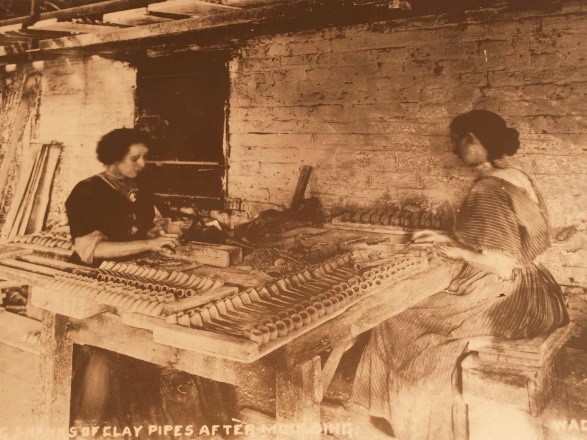

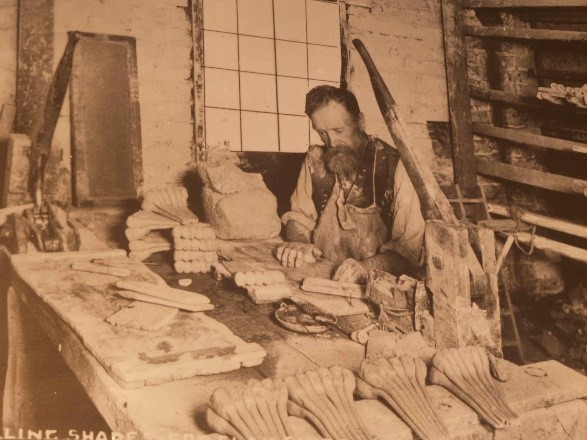

The Tans now homed in on Andrew Curley’s house and the adjacent clay-pipe factory. The factory had a thatched roof which blazed epically that dreadful June night, bringing to an end a business that had been running for over 250 years.

Knockcroghery’s pipe making business was established in the 18th century by a Scotsman called Buckley. By the late 19th century, men and women from all across Connaught were puffing on Knockcroghery pipes. Seven different families were employed in the business, each with their own kiln, producing pipes inscribed with their names – O’Brien, Curley, Cunnane and Murray.[iv] Other pipes bore epic inscriptions such as “Home Rule”, “Who dares speak of ’98?”, “Support Irish industry”, “Repeal” and “Parnell”.

In 1890, a report in the Freeman’s Journal estimated that an astonishing 57,000 tobacco pipes, known as “Dudeens”, were manufactured every week at the factory which was then owned by Andrew Curley’s father William. Almost 100 people were employed, either in the manufacture or distribution, with exports reaching as far away as the US and Australia.[v]

The Tans now homed in on Andrew Curley’s house and the adjacent clay-pipe factory. The factory had a thatched roof which blazed epically that dreadful June night, bringing to an end a business that had been running for over 250 years.

Knockcroghery’s pipe making business was established in the 18th century by a Scotsman called Buckley. By the late 19th century, men and women from all across Connaught were puffing on Knockcroghery pipes. Seven different families were employed in the business, each with their own kiln, producing pipes inscribed with their names – O’Brien, Curley, Cunnane and Murray.[iv] Other pipes bore epic inscriptions such as “Home Rule”, “Who dares speak of ’98?”, “Support Irish industry”, “Repeal” and “Parnell”.

In 1890, a report in the Freeman’s Journal estimated that an astonishing 57,000 tobacco pipes, known as “Dudeens”, were manufactured every week at the factory which was then owned by Andrew Curley’s father William. Almost 100 people were employed, either in the manufacture or distribution, with exports reaching as far away as the US and Australia.[v]

Business waned with the advent of cigarette smoking, but the 1901 census lists sixteen people who were still employed in either pipe making or pipe finishing. By 1911, that figure was down to nine. And on June 21st 1921, it was pointedly reduced to none.

John Murray fared somewhat better than the Curleys. The 51-year-old publican rented a house from the Feeney family in which he ran a pub, grocery and Her Majesty’s post office. As with the priest, this building had a slate roof. When the Tans set his back door alight, Murray reacted quickly and extinguished the flames. Amongst those who witnessed this act was his four-year-old son Jimmy Murray who, two decades years later, captained Roscommon to All-Ireland glory in 1943 and ’44.

According to a contemporary, Knockcroghery presented ‘a shocking appearance’ when morning broke. It was ‘a mass of smouldering ruins, with the occupants of the houses homeless and destitute, all their belongings being consumed in the general conflagration.’ Murrays, Flanagan’s and the priests were spared the worst because of their slate roofs. A small pub and grocery owned by ‘The Widow Murray’ was also left untouched when she showed the Tans her newborn baby son Pat and pleaded with the Tans to have mercy.[vi]

The people of Roscommon were quick to come to Knockcroghery’s aid, bringing clothes and setting up a relief fund. Relatives accommodated some villagers, while others moved to farm buildings that were hastily converted into dwellings. A number of simple stone houses were also built at this time.

Compensation for rebuilding the village was paid under the terms of the 1921 Treaty. In October Andrew Curley’s widow Bridget received £6,190 for the destruction of the pipe factory. Denis O’Brien, draper and publican, was awarded £6,029, Annie Jackson, shopkeeper, secured £6,140, while Pat Fitzgerald and Edward Gordon received £1,221 and £1,014 respectively. Many of the original houses were never re-built and the clay pipe industry was never revived.

Although questions were raised in Westminster about this ‘barbarous outrage’, nobody was ever held accountable for the burning of Knockcroghery. Ironically, the Royal Irish Constabulary and military authorities were assigned to trace the perpetrators.[vii] Contemporary accounts show that while it was blindingly obvious to everyone that the attackers came from the barracks in Athlone, witnesses ‘could not be got to give evidence’.

For further insight into the burning and the claypipe business, visit the Knockcroghery Clay Pipe Visitors’ Centre and Workshop.

With thanks to Ethel Kelly, Mary Claire Greally, Martin Mac Oirealla and Matt Rogers.

[ii] Thomas Stanton Lambert, a decorated veteran of the Western Front, was born in 1871. His father Rev. WM Lambert was a clergyman from Wiltshire. Also in the car were his niece Miss Arthurs and Colonel and Mrs Challoner. Mrs Lambert was said to be utterly distraught by his murder.

[iia] The name of Knockcroghery is particularly dark. ‘Cnoc na Crocaire’ means the Hill of the Hangings and refers to a time when a violent English commander called Sir Charles Coote hanged the O’Kellys of Galey Castle when they refused to submit.

[iii] That the Presbytery did not burn is said to be due to ‘the promptitude of his servants who, with water and sand which was convenient, succeeded in putting out the fire’.

[iv] According to Weld, in 1832, there were eight kilns producing from 100 to 500 gross pipes a week.

In 1837, Samuel Lewis described Knockcroghery as ‘a village in the parish of Killinvoy, barony of Athlone, county of Roscommon and province of Connaught, 5 miles (S E) from Roscommon, containing 180 inhabitants. It consists of 45 houses built on a hill and has fairs on Aug. 22nd and Oct. 25th the latter of which is a large sheep fair. It is a constabulary police station and the manufacture of tobacco-pipes is carried on to a considerable extent.’

The ‘Forty Three’, a soft pipe, was the factory’s bestseller. Knockcroghery developed accordingly with shops, a blacksmith, a mill and millrace, a British Government Post Office and a constabulary Police Barracks, a Church, a Fair Green and a Pound.

[v] Pipes were then a fundamental element of Irish wakes. Literally hundreds of pipes would be filled with cheap twist tobacco and laid out on trays, between whiskey and porter, for the mourners to imbibe at leisure. As each handcrafted pipe was taken up, it was customary for the recipient to say “Lord have mercy” and for many the pipe was simply known as a “Lord ha’ mercy”.

[vi] Pat Murray would grow up to become a well-known and colourful Knockcroghery icon.

[vii] When Wee Joe Devlin, MP, raised the ‘barbarous outrage’ in Westminster on the Wednesday, Mr. Henry said ‘The inhabitants of the village are not able to identify any of the persons who committed these outrages, but the matter is being carefully investigated by the police and military authorities.’

John Murray fared somewhat better than the Curleys. The 51-year-old publican rented a house from the Feeney family in which he ran a pub, grocery and Her Majesty’s post office. As with the priest, this building had a slate roof. When the Tans set his back door alight, Murray reacted quickly and extinguished the flames. Amongst those who witnessed this act was his four-year-old son Jimmy Murray who, two decades years later, captained Roscommon to All-Ireland glory in 1943 and ’44.

According to a contemporary, Knockcroghery presented ‘a shocking appearance’ when morning broke. It was ‘a mass of smouldering ruins, with the occupants of the houses homeless and destitute, all their belongings being consumed in the general conflagration.’ Murrays, Flanagan’s and the priests were spared the worst because of their slate roofs. A small pub and grocery owned by ‘The Widow Murray’ was also left untouched when she showed the Tans her newborn baby son Pat and pleaded with the Tans to have mercy.[vi]

The people of Roscommon were quick to come to Knockcroghery’s aid, bringing clothes and setting up a relief fund. Relatives accommodated some villagers, while others moved to farm buildings that were hastily converted into dwellings. A number of simple stone houses were also built at this time.

Compensation for rebuilding the village was paid under the terms of the 1921 Treaty. In October Andrew Curley’s widow Bridget received £6,190 for the destruction of the pipe factory. Denis O’Brien, draper and publican, was awarded £6,029, Annie Jackson, shopkeeper, secured £6,140, while Pat Fitzgerald and Edward Gordon received £1,221 and £1,014 respectively. Many of the original houses were never re-built and the clay pipe industry was never revived.

Although questions were raised in Westminster about this ‘barbarous outrage’, nobody was ever held accountable for the burning of Knockcroghery. Ironically, the Royal Irish Constabulary and military authorities were assigned to trace the perpetrators.[vii] Contemporary accounts show that while it was blindingly obvious to everyone that the attackers came from the barracks in Athlone, witnesses ‘could not be got to give evidence’.

For further insight into the burning and the claypipe business, visit the Knockcroghery Clay Pipe Visitors’ Centre and Workshop.

With thanks to Ethel Kelly, Mary Claire Greally, Martin Mac Oirealla and Matt Rogers.

Footnotes

[i] Lord Bandon was kidnapped in Cork on the same day.[ii] Thomas Stanton Lambert, a decorated veteran of the Western Front, was born in 1871. His father Rev. WM Lambert was a clergyman from Wiltshire. Also in the car were his niece Miss Arthurs and Colonel and Mrs Challoner. Mrs Lambert was said to be utterly distraught by his murder.

[iia] The name of Knockcroghery is particularly dark. ‘Cnoc na Crocaire’ means the Hill of the Hangings and refers to a time when a violent English commander called Sir Charles Coote hanged the O’Kellys of Galey Castle when they refused to submit.

[iii] That the Presbytery did not burn is said to be due to ‘the promptitude of his servants who, with water and sand which was convenient, succeeded in putting out the fire’.

[iv] According to Weld, in 1832, there were eight kilns producing from 100 to 500 gross pipes a week.

In 1837, Samuel Lewis described Knockcroghery as ‘a village in the parish of Killinvoy, barony of Athlone, county of Roscommon and province of Connaught, 5 miles (S E) from Roscommon, containing 180 inhabitants. It consists of 45 houses built on a hill and has fairs on Aug. 22nd and Oct. 25th the latter of which is a large sheep fair. It is a constabulary police station and the manufacture of tobacco-pipes is carried on to a considerable extent.’

The ‘Forty Three’, a soft pipe, was the factory’s bestseller. Knockcroghery developed accordingly with shops, a blacksmith, a mill and millrace, a British Government Post Office and a constabulary Police Barracks, a Church, a Fair Green and a Pound.

[v] Pipes were then a fundamental element of Irish wakes. Literally hundreds of pipes would be filled with cheap twist tobacco and laid out on trays, between whiskey and porter, for the mourners to imbibe at leisure. As each handcrafted pipe was taken up, it was customary for the recipient to say “Lord have mercy” and for many the pipe was simply known as a “Lord ha’ mercy”.

[vi] Pat Murray would grow up to become a well-known and colourful Knockcroghery icon.

[vii] When Wee Joe Devlin, MP, raised the ‘barbarous outrage’ in Westminster on the Wednesday, Mr. Henry said ‘The inhabitants of the village are not able to identify any of the persons who committed these outrages, but the matter is being carefully investigated by the police and military authorities.’